“Before my diagnosis (of breast cancer), the Gilbert Welch’s book would have held little interest for me because I assumed I was okay and would always be okay.

The subject of cancer screening is very complex and H. Gilbert Welch’s book, Should I Be Tested for Cancer: Maybe Not and Here’s Why does an excellent job of explaining those complexities in a way the average person is able to understand.

AUTHOR: Welch, H. Gilbert

TITLE: Should I be Tested for Cancer: Maybe Not and Here’s Why

Pub Info: Berkeley: University of California Press, c2004

Reading this book has been extremely valuable to me as a breast cancer survivor. It is well researched, well written, and incredibly informative. It will definitely allow me to read potential research articles and the media reports about them with a more critical eye. What I learned will not only help me make better screening decisions but also help me understand the potential problems of overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

The biggest improvement in my knowledge is a better understanding of survival statistics. I can now see that because cancers are now often discovered long before they might become symptomatic, the five-year survival rate is nearly meaningless. It is commonly quoted by the media but does not accurately indicate the actual mortality figures. It is misleading. It was probably relevant years ago when many cancers were advanced when detected and surviving five years often have meant you were “cured.”

The question I would most like to see answered (by Dr. Gilbert Welch or anyone else) is whether or not the new methods of cancer testing reduce mortality for specific cancers. Dr. Welch dedicates only three pages to this question. The first thing he says is “that can be hard to know.” He does say that in the case of colon cancer, the answer is probably yes. With many other cancers, the answer is less obvious.

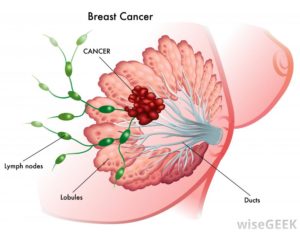

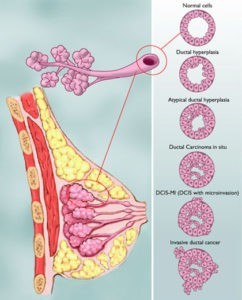

The chapter on pathology was a bit of a shock. Because a pathologist spoke at one of my group meetings, I was aware that not all of the biopsied tumor is tested — generally only six segments if I recall correctly. I also understood that there could be some question from time to time about whether the tumor was malignant or not. I did not realize how much difference of opinion there could be between groups of well-trained pathologists.

I did know that my sister’s DCIS was so small that it was apparently all removed during her biopsy and none could be found in the very large amount of tissue (an approximately 9 cm. chunk) they took for her lumpectomy. They explained to her that they did triple the usual amount of dissections of the sample trying to find more DCIS.

I still have questions about my thirteen years of mammograms before my cancer was detected. I would probably have made different decisions about getting them if I had read this book before my own breast cancer diagnosis. At the time I felt that cancer was way down on the list of possible ways that I might die. Now, I consider cancer a threat to my longevity. Even though it was easily possible to feel cancer in my breast, I did not know it was there until it was revealed on my annual mammogram. However, the mammograms had not seen anything suspicious in the previous years. Never the less, I think it is quite likely that the last mammogram had a roll in extending my life, or at least from keeping the malignancy from progressing to other parts of my body.

Before my diagnosis, the book would have held little interest for me because I assumed I was okay and would always be okay. The idea that I would get breast cancer scarcely entered my mind. I was having the mammograms only because the doctor suggested them. However, if I had been privy to the facts about cancer testing and statistics I might have decided not to be tested. In my case, I think that could have been a mistake. On the other hand, I was 53 when diagnosed and that is just past the age when the proposed new guidlines would have a woman with no history of breast cancer in her family begin mammography. I could have avoided the first ten mammograms.

I wish that the mainstream media that informs most of us would do a much better job of getting out the news that cancer survival statistics can be misleading and that in spite of increasingly sophisticated ways of finding early cancer, in general, it seems possible that in many cases no fewer people are dying from their disease because it was discovered sooner, and many unnecessary and harmful treatments are being done on those who would never have died from their disease if it was left undetected. However, it took this entire complex book to educate me. I discover as I am trying to write a summation of the book that it is difficult because there are so many layers of understanding necessary to explain why getting tested may not always be the best decision. That’s why I suggest it as such a good resource.

I do have two criticisms of the book.

The first is that on page 163 Dr. Welch suggests that “some mammographically detected cancers be best treated not by surgery, but with hormonal manipulation (i.e., by stopping estrogen for those women who are on it and/or giving an antiestrogen like Tamoxifen).” Yes, supplementary estrogen should definitely be stopped. However, removing the estrogen from one’s body with Tamoxifen or the newer anti-estrogen drugs is not a benign treatment. If I had DCIS or a very small invasive tumor I would much rather have a lumpectomy than take five years of such a life-altering drug. Or, knowing what I know now, I would very likely decide to take the “watch and wait” approach to mammographically detected DCIS. Perhaps Dr. Welch is unaware of the tremendous physical and mental side-effects of these drugs or perhaps he feels that surgery is a riskier option. Hormonal manipulation was the most difficult part of my cancer treatments.

My second criticism is that I wish more empathy had been displayed for those in the cancer world. An example is on page 32 when Dr. Welch says, “any given cancer is a relatively rare cause of death in general . . .” This gave me pause while I was reading and I thought of the dozens of women I know who have died decades before their time from various cancers. It seems a huge problem to me. I realize I know more women with cancer than most because of the groups I belong to, but four of these women were neighbors and friends I know from my own block. I don’t know if early testing could have saved them, but I do know that to me their deaths do not seem “rare.”

In this same vein on page 187 in his section on “Wrong Reasons to be Tested,” he says the following:

“The powerful (and misleading) personal anecdote. You have heard the stories, whether from friends and acquaintances or propagated in the media. A person whose “life was saved by a test”; another who died simply because his cancer wasn’t caught early.” That’s powerful stuff. But while the facts of the individual cases may not be accurate, the conclusions that cancer testing must save lives is not.

Stories are not a reason to get tested for cancer. People whose lives were allegedly [BAD choice of words in my opinion because it sounds like someone is on trial – the word presumably would be far less inflammatory] saved may not have needed treatment, or they may have been treated just as successfully years later. Or they may die of their cancer anyway and simply end up having known about it longer. People whose lives were allegedly lost by the lack of testing may not have been treated more successfully with early diagnosis, or testing may have missed the cancer. The reason to get tested for cancer is because it really saves lives (something that takes thousands of lives to prove), not because someone testifies that her own life was saved or that someone else’s could have been.”

I agree with Dr. Welch for the most part. I don’t know with absolute certainty that my life was “saved by a test.” Perhaps I would have noticed that lump with my next shower. Perhaps it was

not destined to move outside my breast, although it was considered rather aggressive at pathology. Perhaps, unknown to me and my doctors, it has actually metastasized and will eventually kill me in spite of my treatment. One of my neighbors who died had regular mammograms and they did not save her. That is a personal anecdote, but it is important to me. I, personally, have decided not to be tested for metastases because I do not believe that finding them early would extend my life.

My sister’s life was not at risk because of her DCIS. Perhaps she would have been better off not to know of its existence. At first she was extremely frightened by the notion of cancer and was ready to make a rash decision (double mastectomy!). She had heard the “cancer” word. Fortunately, the medical world moved slowly and she had the time and ability to research. Armed with this knowledge she chose a lumpectomy and turned down radiation and tamoxifin. She was able to make her own decisions. She is currently reading this book and I am looking forward to finding out if, knowing what she knows now, she would make different decisions. My guess is that she would not. Nor would I.

This brings me to my main point. I want to have a choice about how to be tested and/or treated. I want to know the facts about testing (and this book is the best and most informative thing I have read) and possible treatments and make my OWN decisions based on the infomation I have been able to gather from both the medical communicty and my own research. However, I know that not every individual has the time, inclination, or ability to research and find out what is best. The medical community must make testing and treatment recommendations. At the same time, the medical community must make wise treatment decisions that will be more helpful than harmful to patients.

Mary Miller-Breast Cancer Profile in Courage