Overall, the 15-year breast cancer mortality rate was 2.33 percent for patients treated with lumpectomy alone, 2.26 percent for patients treated with mastectomy alone, and 1.74 percent for patients treated with lumpectomy and radiation. For all participants, the cumulative mortality rate was 2.03 percent.

In women younger than the age of 50, black women and women with estrogen receptor-negative cancers, radiotherapy had an even greater impact on breast cancer-specific mortality.

“On average, 370 women would need to be treated with radiotherapy to save one life,” the authors wrote. “This count was fewer for black women (115 treated) and for women younger than 50 years (63 treated).”

Similar results have also been reported in patients with invasive cancer, Giannakeas and colleagues added. What leads to these results, however, remains something researchers must investigate further.

“Although the clinical benefit is small, it is intriguing that radiotherapy has this effect, which appears to be attributable to systemic activity rather than local control,” the authors concluded. “How exactly radiotherapy affects survival is an important question that should be explored in future studies.”

“Recent media reports of potential misdiagnosis and overtreatment of early-stage breast cancer (DCIS) may be frightening women away from recommended screening for breast cancer…”

Rather than forgo screening for breast cancer because of fears of being misdiagnosed and receiving unnecessary therapy, women should know what questions to ask and be confident about weighing their options, the release emphasizes.

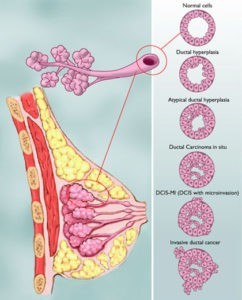

The joint statement was released primarily in response to a recent article in the New York Times, which described the disturbing case history of a woman misdiagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). The patient had a “golf-ball sized” section of her breast removed, underwent radiation and chemotherapy, and then was told a year later that she never had cancer.

According to the article, the patient stated that the fear was the worst of all. “Psychologically, it’s horrible…. I should never have had to go through what I did,” she said.

The New York Times article highlights an issue that is a subject of much discussion among oncologists. Advances in mammography and other imaging technology during the last 3 decades have allowed visualization of extremely small lesions, according to the article. It may be particularly challenging for pathologists to distinguish the difference between some benign lesions and early-stage breast cancer.

Mary Miller- Breast Cancer Profile in Courage

“The mortality rates by age were used to estimate how many women died of causes other than breast cancer during the lead time afforded by screening mammography. Resulting age-dependent overdiagnosis rates, along with screen-detected breast cancer incidence by age, were used to estimate type 1 overdiagnosis rates for the U.S. screening population…”

“Mammograms with false-positive results were associated with increased short-term anxiety for women, and more women with false-positive results reported that they were more likely to undergo future breast cancer screening. A portion of women who undergo routine mammogram screening will experience false-positive results and require further evaluation to rule out breast cancer…”

Recent media reports of potential misdiagnosis and overtreatment of early-stage breast cancer may be frightening women away from recommended screening for breast cancer, according to a joint news release from Susan G. Komen for the Cure and the College of American Pathologists.

“Nearly a year earlier, in 2007, a pathologist at a small hospital in Cheboygan, Mich., had found the earliest stage of breast cancer from a biopsy. Extensive surgery followed, leaving Ms. Long’s right breast missing a golf-ball-size chunk.

Now she was being told the pathologist had made a mistake. Her new doctor was certain she never had the disease, called ductal carcinoma in situ, or D.C.I.S. It had all been unnecessary — the surgery, the radiation, the drugs and, worst of all, the fear.

“Psychologically, it’s horrible,” Ms. Long said. “I never should have had to go through what I did.”

Flip of a Coin

The diagnosis of DCIS “is a 30-year history of confusion, differences of opinion and under- and overtreatment,” said Shahla Masood, MD, the head of pathology at the University of Florida College of Medicine in Jacksonville, in the New York Times article. “There are studies that show that diagnosing these borderline breast lesions occasionally comes down to the flip of a coin.”

In response to concerns about the accuracy of breast pathology, the College of American Pathologists has announced that it will begin a voluntary certification program for pathologists who read breast samples. Among the requirements is that pathologists must read 250 breast cases a year. In addition, in a response to concerns that approximately 17% of DCIS cases identified by needle biopsy may be misdiagnosed, a new study supported by the federal government will be conducted to examine the variations in breast pathology.

However, as noted in the New York Times article, there are currently no mandated diagnostic standards or requirements for pathologists who evaluate breast tissue samples. This means that diagnostic accuracy can vary among facilities, depending on the individual expertise of the pathologists.

Is DCIS Really a Cancer?

As previously reported by Medscape Medical News, some experts believe that the term “carcinoma” in the phrase “ductal carcinoma in situ” is misleading and troubling and ought to be dropped, or at least that its elimination should be considered. In fact, in some cases experts suggest that DCIS is a possible candidate for management by active surveillance — a treatment strategy of growing importance in prostate cancer in which low-risk patients are monitored but do not receive active treatment unless they progress to a higher risk.

However, others disagree. “Although active surveillance is a step that can mitigate the harms of treatment, we doubt that it will mitigate the effects of uncertainty and anxiety,” H. Gilbert Welch, MD, Steven Woloshin, MD, and Lisa M. Schwartz, MD, from the Department of Veterans Affairs and Dartmouth Medical School, New Hampshire, comment in an editorial (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:228-229).

“To do this, we must go back a step and question the value of making the diagnosis in the first place,” they write.

The editorialists note that there “is a sea of uncertainty surrounding DCIS. Some lesions will progress to cancer, others will not. Some women with DCIS will develop cancer elsewhere in their breasts, whereas others will not. And we’re not sure what the chances are.”

For more articles like this, click here: http://peoplebeatingcancer.org/search/node/DCIS