Have you discovered that you have Lynch Syndrome and have an increased risk of several different types of cancer? Though I do not have Lynch Syndrome I do live with an increased risk of many different types of cancer.

I was diagnosed with a blood cancer called multiple myeloma in 1994, underwent aggressive chemotherapy, radiation and an autologous stem cell transplant. As a result of all that toxicity I live with an increased risk of several cancers as well as a risk of relapse of my primary cancer, multiple myeloma.

I live an anti-cancer lifestyle pursuing a host of evidence-based, non-conventional therapies such as curcumin and resveratrol (see the third study linked below). I’ve lived cancer-free since early 1999.

My point is that just living with an increased risk of cancer does not mean that a cancer diagnosis is a certainty. And I am tested annually. Lifestyle and regular diagnostic testing is my answer to my risk of cancer.

Lynch Syndrome, also known as Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC), is a hereditary genetic condition that increases the risk of developing several types of cancer, particularly colorectal cancer and endometrial cancer. It is caused by mutations in certain genes, most commonly in the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 genes.

The increased risk of cancer associated with Lynch Syndrome can vary depending on the specific gene mutation and the individual’s family history. In general:

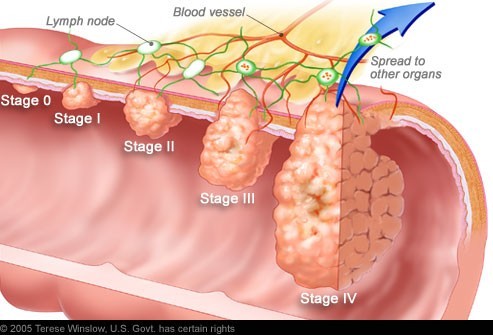

- Colorectal Cancer: Individuals with Lynch Syndrome have a significantly elevated risk of developing colorectal cancer. The risk is estimated to be up to 80% over a person’s lifetime, which is substantially higher than the general population.

- Endometrial Cancer: Women with Lynch Syndrome have a higher risk of developing endometrial (uterine) cancer. The lifetime risk for endometrial cancer in women with Lynch Syndrome is estimated to be around 40-60%, compared to about 2-3% in the general population.

- Other Cancers: Lynch Syndrome can also increase the risk of other cancers, including ovarian, stomach, small intestine, liver, gallbladder ducts, urinary tract, and brain.

It’s important to note that not everyone with Lynch Syndrome will develop cancer, and the specific risks can vary based on factors like the specific gene mutation, family history, and lifestyle factors. Additionally, regular screening and surveillance can help detect and manage potential cancers at an earlier, more treatable stage.

To learn more about colorectal cancer, read the posts linked below-

If you suspect you may have Lynch Syndrome or have a family history of it, it’s crucial to consult with a genetic counselor or healthcare professional who can provide personalized information and guidance based on your specific situation. They can help you understand your risks and develop a plan for screening and prevention.

David Emerson

- Cancer Survivor

- Cancer Coach

- Director PeopleBeatingCancer

“Lynch syndrome (HNPCC or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) is an autosomal dominant genetic condition that has a high risk of colon cancer[1] as well as other cancers including endometrial cancer (second most common), ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, upper urinary tract, brain, and skin. The increased risk for these cancers is due to inherited mutations that impair DNA mismatch repair. It is a type of cancer syndrome…”

“The majority of people who develop colorectal cancer don’t have a family history that puts them at increased risk for the fourth most common type of cancer in both men and women. However, 5 to 10 percent of colorectal cancer cases are due to inherited causes.

Lynch syndrome accounts for about 3 percent of all newly diagnosed cases of colon cancer and 2 percent of endometrial cancers. Syngal says your increased risk for colorectal cancer depends on the underlying genes; some increase your risk as much as 50 to 80 percent…

New data show that 1 out of 279 people in the general population has Lynch syndrome…

People with Lynch syndrome often develop more than one primary type of cancer and tend to be diagnosed with cancer at younger ages. In fact, they have a 70 percent lifetime risk of developing any of the Lynch-associated cancers, including-

- colorectal,

- endometrial,

- ovarian,

- stomach,

- biliary tract,

- urinary tract,

- brain and

- sebaceous skin cancers.

Could You Have Lynch Syndrome?

Just because you have a cancer-predisposing mutation doesn’t mean you’ll automatically develop cancer; it just increases the likelihood you will. Lynch syndrome is caused by a germline mutation (one that’s transmitted to offspring) in one of the DNA mismatch repair genes, which repairs replication-associated errors.

If one of your parents has Lynch syndrome, you have a 50 percent chance of inheriting it. Furthermore, even second- and third-degree relatives have an increased risk of inheriting Lynch syndrome.

The good news is that if you know you have Lynch syndrome, you can take steps to screen for, and prevent, colorectal cancer. That’s why genetic testing is important…

What Should You Do if You Have Lynch Syndrome?

Normally, colorectal cancer develops slowly, which is why doctors recommend a 10-year interval for colonoscopies in people at average risk who have a normal screening test. However, colorectal cancer develops rapidly in people with Lynch syndrome, so Syngal says early and frequent screening is important. She recommends people with Lynch syndrome undergo a colonoscopy every one to two years beginning at age 25 (instead of 50 for people at average risk).

Women with Lynch syndrome should also begin screening for endometrial cancer around age 30 or 35 and possibly undergo a preventive hysterectomy once they’re finished having children. Syngal recommends men and women undergo screening for stomach cancer via endoscopybeginning in their early 30s.

“Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a second leading cause of cancer deaths in the Western world. Currently there is no effective treatment except resection at a very early stage with or with-out chemotherapy. Of various epithelial cancers, CRC in particular has a potential for prevention, since most cancers follow the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, and the interval between detection of an adenoma and its progression to carcinoma is usually about a decade. However no effective chemopreventive agent except COX-2 inhibitors, limited in their scope due to cardiovascular side effects, have shown promise in reducing adenoma recurrence. To this end, natural agents that can target important carcinogenic pathways without demonstrating discernible adverse effects would serve as ideal chemoprevention agents…”