Diagnosed with Cancer? Your two greatest challenges are understanding cancer and understanding possible side effects from chemo and radiation. Knowledge is Power!

Learn about conventional, complementary, and integrative therapies.

Dealing with treatment side effects? Learn about evidence-based therapies to alleviate your symptoms.

Click the orange button to the right to learn more.

- You are here:

- Home »

- Blog »

- side effects ID and prevention »

- Napping and Heart Health

Napping and Heart Health

How does my occasional daytime napping affect my heart health? I ask because I am a long-term cancer survivor who was diagnosed with chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy in late 2010. Cardiotoxic chemo regimens did a number on my heart.

I manage my CIC, and chronic atrial fibrillation with evidence-based non-conventional heart therapies such as:

- moderate, daily exercise,

- a heart healthy diet (Mediterranean Diet mostly)

- heart healthy nutritional supplementation

And here’s the kicker. When I was first diagnosed with CIC, I was put on metoprolol and I immediately experienced side effects.

So I decided not to undergo any conventional heart meds If I could help it. And this attitude puts more pressure on evidence-based non-conventional heart health therapies like exercise, napping, etc.

How does daytime napping affect heart health?

Daytime napping can have various effects on heart health, depending on factors such as duration, frequency, and individual health status. Here are some potential impacts:

- Positive Effects:

- Stress Reduction: Short naps can help reduce stress levels, which in turn may lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of heart disease, improving heart health.

- Improved Alertness: A brief nap can enhance alertness and cognitive function, potentially reducing the likelihood of accidents or errors that could indirectly impact heart health.

- Negative Effects:

- Long Naps: Prolonged napping, especially if it exceeds 45-60 minutes, may be associated with an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, and overall mortality. Some studies suggest that long naps may disrupt nighttime sleep patterns and lead to metabolic changes that are detrimental to cardiovascular health.

- Sleep Disorders: Excessive daytime napping could be a symptom of sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, which is linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular problems.

- Inactivity: Spending long periods of time napping during the day may contribute to a sedentary lifestyle, which is a risk factor for heart disease.

- Individual Variations:

- The effects of daytime napping can vary from person to person. Some individuals may benefit from short, strategic naps to boost productivity and well-being, while others may experience negative effects on sleep quality or daytime functioning.

Based on the study linked and excerpted below, in-frequent occasional naps that are not too long are okay for my heart health. Good.

How about you? How is your heart health? do you undergo daily naps? Do you undergo other evidence-based non-conventional therapies?

If you’d like to learn more about evidence-based non-conventional heart health therapies send an email; to David.PeopleBeatingCancer@gmail.com

Good luck,

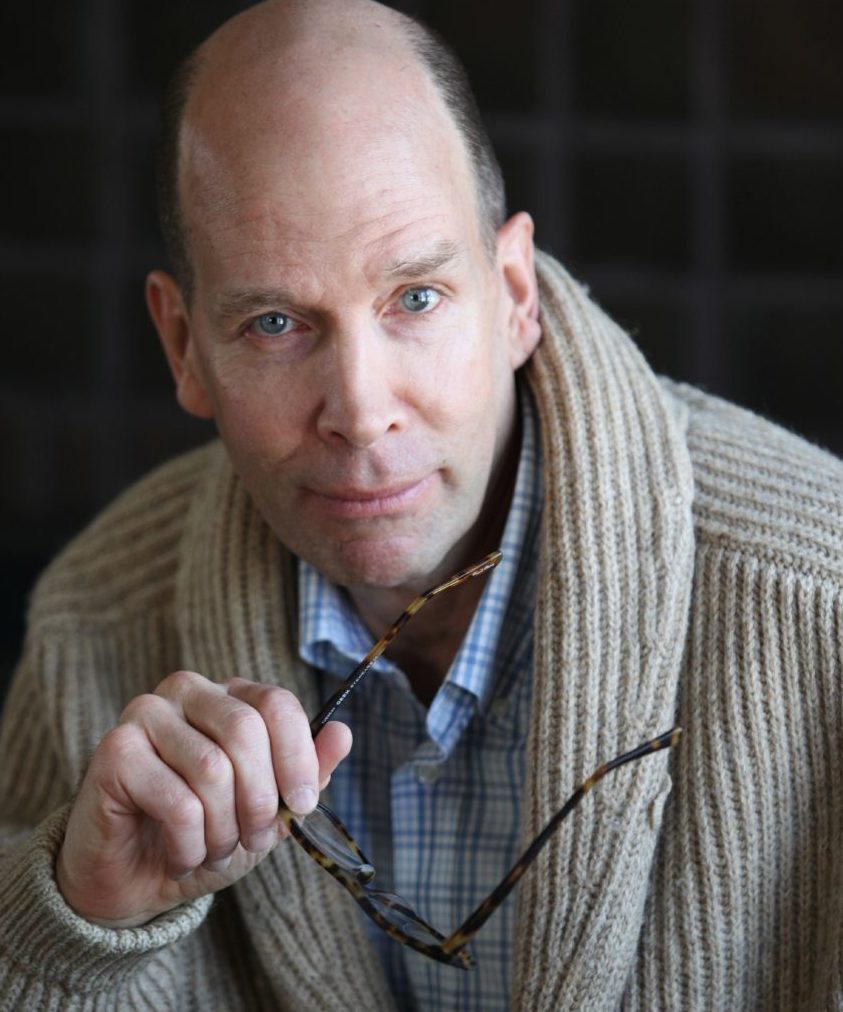

David Emerson

- Cancer Survivor

- Cancer Coach

- Director PeopleBeatingCancer

Association of napping with incident cardiovascular events in a prospective cohort study

“Nap frequency and incidence of CVD events-

Subjects napping once or twice weekly had a lower risk of developing any CVD event compared with non-nappers. This finding is comparable with the result of the Greek cohort study taking nap frequency into account, as they reported lower coronary mortality for subjects napping once or twice weekly compared with non-nappers.4

The other study taking nap frequency into account did not differentiate between napping 1–2 times and 3–5 times per week and found no effect of irregular nappers (≤5 times weekly) on CVD mortality.9

Although taking 1–2 naps weekly was no longer associated with CVD events in some sensitivity analyses (>65 years old or adjustment for OSA), this was most likely due to the low number of subjects included in these analyses (n=903 and n=1659, respectively): this led to relatively wide CIs while the effect size remained stable when adjusting for OSA.

Another possible explanations is that older nappers do not have time constraints regarding napping and thus take longer naps, which have previously been associated with CVD.11 13 Further, older nappers have more comorbidities and the negative association between occasional naps and CVD might be weaker in this population.

In the crude model, we observed a J curved relationship between nap frequency and incidence of CVD events.

Interestingly, this finding is in line with previous studies reporting a J curved relationship between nap duration and CVD11 and cardiovascular risk factors, such as diabetes and metabolic syndrome.12 However, the increased risk of CVD events for frequent nappers disappeared in adjusted analyses. Regarding the underlying causes of our findings, we could speculate that frequent napping may be secondary to impaired sleep quality due to a chronic condition, which may represent an independent risk factor for CVD events.

In contrast, occasional napping might be a result of a physiological compensation allowing for a decrease in stress due to insufficient nocturnal sleep and thus could have a beneficial effect on CVD events. Although the blood pressure and heart rate surge following awakening after an afternoon naps might increase cardiovascular risk in the short term,25 the stress releasing result of occasional naps26 27 might counteract this effect and explain the lower risk of CVD events for occasional nappers compared with non-nappers.

Interestingly, the beneficial effect of napping once or twice weekly on CVD remained even after controlling for major cardiovascular risk factors, OSA or excessive daytime sleepiness, confounders other studies did not control for.

Nap duration and incidence of CVD events

We found no association between daily nap duration over a week and incident CVD events. Our findings are partly in line with a meta-analysis, which found no association between short naps (<1 hour) and CVD, but contradict their finding that long naps (≥1 hour) were positively associated with CVD.11

Interestingly, they found a significant J curved dose–response relationship between nap duration and CVD11; the CVD risk decreased for napping 0–30 min/day, slightly increased for 45 min/day napping followed by a sharp increase for longer nap durations.

Also, our findings are not in line with a previous German study reporting an increased risk of coronary artery disease among subjects taking long naps (poor heart health) (>1 hour) at least five times per week.9 Further, our findings do not replicate those of previous studies reporting either an adverse dose–response effect of nap duration on CVD13 or a protective dose–response effect of nap duration on coronary mortality.4

However, these studies did not control for important confounders, such as physical activity,9 13 sleep duration4 and major cardiovascular (heart health) risk factors.4 Further, the meta-analysis included heterogeneous studies regarding confounders.11 Also, publication bias might exist, leading to an overestimation of an effect.28″