Immunotherapy as a multiple myeloma treatment is new as of the writing of this post (early 2020). The first article linked and excerpted below cites a phase one trial involving 11 relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma survivors.

The scenario outlined in the second article below happened to a close friend of mine. Mitch (not his real name) developed advanced bladder cancer. Mitch underwent surgery and several courses of standard-of-care chemotherapy.

As often happens, Mitch developed an infection after his last course of chemotherapy. Mitch’s oncologist determined that standard chemotherapy was not working to slow Mitch’s advanced bladder cancer so he switched Mitch to an immunotherapy (Keytruda). Mitch began Keytruda therapy a couple of weeks following his antibiotic therapy.

I’ve been living with multiple myeloma since my diagnosis in early 1994. I’ve been working with fellow cancer patients, survivors and caregivers since the launch of PeopleBeatingCancer in June of 2004.

In all that time I’ve never seen a case when the patient’s needs didn’t go beyond conventional oncology-

all therapies needed in addition to conventional cancer therapy including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation.

As a cancer therapy and certainly as a multiple myeloma treatment, immunotherapy holds great promise. Unfortunately, it takes time to research the short, long-term and late-stage side effects of every new therapy. Time, research and patient experiences like Mitch’s.

If you undergo immunotherapy as a multiple myeloma treatment, consider a low-tech aka old school idea- the condition of your gut flora.

“The 11 patients had already received multiple myeloma treatment after treatment for their cancer, some as many as 20 different courses of therapy. Yet their myelomas, almost all classified by doctors as “high risk,” kept coming back. Their options faded away.

The industry-funded study was designed to find a safe dose of the experimental immunotherapy, not test its effectiveness. So these first participants got just a low dose, lower than previous studies had suggested could have much of an effect on this blood cancer…”

“Antibiotic use is known to have a near-immediate impact on our gut microbiota and long-term use may leave us drug-resistant and vulnerable to infection.

Now there is mounting laboratory evidence that in the increasingly complex, targeted treatment of cancer, judicious use of antibiotics also is needed to ensure these infection fighters don’t have the unintended consequence of also hampering cancer treatment, scientists report.

Any negative impact of antibiotics on cancer treatment appears to go back to the gut and to whether the microbiota is needed to help activate the T cells driving treatment response…

They (oncologists) have some of the first evidence that in some of the newest therapies, the effect of antibiotics is definitely mixed. Infections are typically the biggest complication of chemotherapy, and antibiotics are commonly prescribed to prevent and treat them.

“We give a lot of medications to prevent infections,” says Dr. Locke Bryan, hematologist/oncologist at the Georgia Cancer Center and MCG.

“During some multiple myeloma treatment white blood cell counts can go so low that you have no defense against bacteria, and that overwhelming infection can be lethal,” says Bryan, a study co-author.

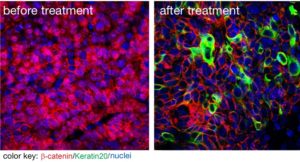

In this high-stakes arena, where chemotherapy is increasingly packaged with newer immunotherapies, Bryan, Zhou and their colleagues have more evidence that antibiotics’ impact on the microbiota can mean that T cells, key players of the immune response, are less effective and some therapies might be too.

They report that antibiotic use appears to have a mixed impact on an emerging immunotherapy called adoptive T-cell therapy, in which a patient’s T cells are altered in a variety of ways to better fight cancer…

“It is clear in animal models that if you wipe out the intestinal microbiota like you do with antibiotics, it will attenuate the chemotherapy efficacy,” says Zhou. “There is also emerging clinical evidence showing that for CTX-based chemotherapy, some patients who also get antibiotics for a longer period of time, seem to have less optimal outcomes…”

While even a single course of antibiotics has been shown to disrupt the microbiota in humans, Zhou has shown in mice that it is protracted use that likely also impacts the immune response. And, when mice, at least, have a weakened immune system their microbiota literally looks different and there is evidence that antibiotics suppress their immune response.

Even with antibiotics out of the equation, there can be conflicting crosstalk between chemotherapy and immunotherapy. If/when chemotherapy hampers the immune response it could obviously impact the efficacy of some immunotherapies. So scientists and clinicians alike also are trying to figure out how best to combine these different therapies, to achieve optimal synergy…”

“Melanoma patients’ response to a major form of immunotherapy is associated with the diversity and makeup of trillions of potential allies and enemies found in the digestive tract…

This connection between a person’s microbiome – trillions of bacteria harbored to varying degrees in the human body – and immune system could have major implications for cancer prognosis and treatment.

“Anti-PD1 immunotherapy is effective for many, but not all, melanoma patients and responses aren’t always durable,..””